A Nuanced Perspective

The idea that a larger sample size leads to more accurate statistical analysis is a cornerstone in the field of statistics and data science. It’s a principle taught in introductory courses and often cited in research papers and industry reports. The logic seems straightforward: the more data you have, the closer you get to representing the true nature of the population you’re studying. This belief influences decisions in various sectors, from healthcare and manufacturing to energy and logistics. Researchers allocate resources, time, and effort to collect larger samples, all in the pursuit of accuracy.

However, the relationship between sample size and accuracy is not as straightforward as it may appear. This article aims to challenge this conventional wisdom and provide a more nuanced perspective. We will delve into the mathematical principles that govern sample size, discuss the limitations of relying solely on large samples, and explore the importance of data quality and experimental design. By the end of this article, the goal is to equip you with a more comprehensive understanding of how sample size impacts statistical analysis, and why bigger isn’t always better.

Key Definitions: Sample vs. Sample Space

Before diving into the complexities of sample size and its impact on statistical analysis, it’s essential to clarify some key terms that often get used interchangeably but have distinct meanings: “sample” and “sample space.”

What is a Sample?

In statistics, a sample refers to a subset of a population that is selected for analysis. The purpose of taking a sample is to draw inferences about the larger population from which it is drawn. For example, if you’re conducting a survey to understand public opinion on a particular issue, the responses from a group of participants represent your sample. The quality and representativeness of the sample are crucial for the validity of the conclusions drawn from the analysis. Sample space refers to the set of all possible outcomes or results that could occur in a statistical experiment. For instance, if you’re flipping a coin, the sample space consists of two outcomes: heads or tails. In a medical trial, the sample space could include all possible health outcomes for patients, ranging from full recovery to no change to adverse effects. Unlike a sample, which is a subset of a population, the sample space is a theoretical construct that encompasses all conceivable outcomes.

Why Both Matter for Accurate Statistical Analysis

Understanding the difference between a sample and sample space is crucial for several reasons. First, conflating the two can lead to incorrect interpretations of data. For example, if you’re analyzing the efficacy of a new drug, your sample might consist of a group of patients who have taken the medication. However, the sample space would include not just those who improved but also those who experienced no change or even deteriorated. Failing to consider the entire sample space could result in a skewed understanding of the drug’s effectiveness.

Second, the quality of your sample is highly dependent on the comprehensiveness of your sample space. If your sample space is too narrow, you risk missing out on possible outcomes, which can lead to biased or inaccurate conclusions.

In summary, while a sample provides the data points for analysis, the sample space sets the theoretical framework within which the analysis occurs. Both are integral to the process of statistical analysis, and understanding their roles and limitations is key to achieving accurate and meaningful results.

The Difference Between Precision and Accuracy

In the discourse surrounding statistics and data analysis, the terms “precision” and “accuracy” are often used interchangeably. However, in the statistical context, these terms have distinct meanings, and understanding the difference between them is crucial for interpreting results correctly.

What is Precision?

Precision refers to the closeness of multiple measurements to each other. In other words, if you were to conduct the same experiment or survey multiple times, a high level of precision would mean that the results are very similar each time. Precision is about consistency and repeatability; it tells us how much the data points in a sample deviate from the mean of the sample. Mathematically, this is often quantified using the standard deviation or the standard error, which provide measures of the dispersion or spread of the data points around the mean.

What is Accuracy?

Accuracy, in contrast, refers to how close a measurement is to the true or actual value. In statistical terms, accuracy is about the closeness of the sample estimate to the true population parameter. For example, if you’re measuring the average height of adults in a city, an accurate measurement would be one that is very close to the true average height of all adults in that city. Unlike precision, accuracy is not concerned with the spread of values but rather with how correct or truthful the values are.

Why They Are Not Synonymous

The distinction between precision and accuracy becomes crucial when interpreting the results of a statistical analysis. It’s entirely possible for a study to be precise but not accurate. For instance, if you’re using a biased sampling method, you might get very consistent results (high precision) that are consistently wrong (low accuracy). Conversely, a study can be accurate but not precise if the results, while close to the true value, show a lot of variability.

In practical terms, a highly precise but inaccurate study could lead to consistent yet wrong conclusions, which could be misleading. On the other hand, an accurate but imprecise study might offer a glimpse of the truth but lack the reliability needed for confident decision-making.

Therefore, in statistical analysis, it’s not enough to aim for either precision or accuracy; both are needed for a comprehensive, reliable, and truthful understanding of the data. Understanding the difference between these two concepts is essential for anyone engaged in research, data analysis, or interpretation of statistical results.

The Mathematics of Sample Size

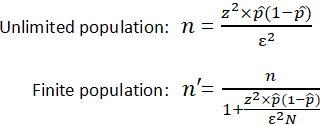

When discussing the impact of sample size on statistical analysis, it’s crucial to delve into the mathematical principles that govern this relationship. One of the key formulas that statisticians use to understand the variability in a sample is the formula for standard error. Additionally, it’s important to recognize the concept of diminishing returns when increasing sample size, as it challenges the notion that simply adding more data points will linearly improve the accuracy of the study.

The Formula for Standard Error

The standard error is a measure that quantifies the variability or dispersion of a sample statistic, such as the sample mean, around the population parameter. The formula for calculating the standard error of the sample mean is:

\[\text{Standard Error (SE)} = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}}\]Here,σ represents the population standard deviation, and n is the sample size. The standard error gives us an idea of how much the sample mean is expected to vary from the true population mean. A smaller standard error implies that the sample mean is a more accurate estimate of the population mean.

Diminishing Returns in Increasing Sample Size While it might seem logical to assume that continually increasing the sample size will proportionally decrease the standard error, the formula shows that this is not the case. The standard error is inversely proportional to the square root of the sample size \(\sqrt{n}\). This means that to halve the standard error, you would need to quadruple the sample size.

For example, if you start with a sample size of 100, you would need to increase it to 400 to halve the standard error, then to 1600 to halve it again. This demonstrates the concept of diminishing returns: each incremental increase in sample size yields a smaller reduction in standard error.

The principle of diminishing returns is especially important in practical applications where resources such as time and money are limited. It suggests that beyond a certain point, the benefit gained from increasing the sample size may not justify the additional resources required.

In summary, while increasing the sample size does reduce the standard error, the relationship is governed by the square root function, leading to diminishing returns. Understanding this mathematical nuance is essential for making informed decisions about sample size in research and data analysis.

When Large Samples Can’t Save You

The allure of large samples often creates a false sense of security, leading to the assumption that a bigger sample size will automatically correct for any shortcomings in the data or methodology. However, this is far from the truth. Even with a large sample, certain statistical rules and assumptions must be met for the analysis to be valid. Violating these assumptions can lead to misleading or incorrect conclusions, regardless of how large the sample is.

Statistical Rules and Assumptions for Valid Analysis

Statistical tests often come with a set of underlying assumptions that must be satisfied for the test results to be valid. Some of the most common assumptions include:

- Normality: The data should be normally distributed, especially for small samples.

- Homoscedasticity: The variance of the errors should be constant across all levels of the independent variable.

- Independence: The observations should be independent of each other.

Large Samples Can’t Correct Violations

Even with a large sample size, violating these assumptions can lead to skewed or misleading results. For instance, if your data is not normally distributed, using statistical tests that assume normality can lead to incorrect inferences. Similarly, if the data violates the assumption of homoscedasticity, the results may underestimate or overestimate the true effect size.

Examples of Common Violations

-

Non-Normality: In medical research, variables like blood pressure or cholesterol levels may not be normally distributed in the population. Using a large sample won’t correct this issue, and specialized non-parametric tests may be required.

-

Heteroscedasticity: In economic studies, the variance of income or expenditure might change with the level of income, violating the assumption of constant variance. A large sample size won’t automatically correct for this.

-

Lack of Independence: In longitudinal studies, observations from the same individual at different time points are not independent. A large sample size won’t resolve this issue, and specialized statistical methods like mixed-effects models may be needed.

In summary, while a large sample size offers many advantages, it is not a panacea for all statistical challenges. Understanding the underlying assumptions and limitations of statistical methods is crucial for conducting valid and reliable research. Even with a large sample, failing to meet these assumptions can lead to erroneous conclusions, underscoring the importance of a well-designed experimental approach.

The Pitfalls of Large Sample Sizes

The quest for larger sample sizes is often driven by the belief that more data will invariably lead to better results. While it’s true that larger samples can provide more robust estimates, they also come with their own set of challenges and pitfalls. Two of the most notable issues are the risk of overfitting and the phenomenon of detecting statistically significant but practically irrelevant differences.

The Risk of Overfitting

Overfitting occurs when a statistical model captures not just the underlying trend in the data but also the random noise. In essence, the model becomes too tailored to the sample data, reducing its ability to generalize to new or unseen data. This is especially problematic in machine learning and predictive modeling, where the goal is often to make accurate predictions on new data.

\[\text{Overfitting:} \quad \text{Model captures both signal and noise, reducing generalizability}\]Large sample sizes can exacerbate the risk of overfitting because they provide more data points, making it easier for the model to fit the noise. While techniques like cross-validation can help mitigate this risk, it’s important to be aware that a large sample size is not a safeguard against overfitting.

Statistically Significant but Practically Irrelevant Differences

Another pitfall of large sample sizes is the detection of differences that are statistically significant but practically irrelevant. In a large sample, even tiny differences between groups can become statistically significant simply because of the sheer volume of data. However, statistical significance does not necessarily imply practical or clinical significance.

\[\text{Statistical Significance} \neq \text{Practical Significance}\]For example, in a medical trial with thousands of participants, a medication might show a statistically significant reduction in blood pressure compared to a placebo. However, if the actual reduction is minuscule, say 1 mm Hg, the result, while statistically significant, may not be clinically relevant.

While large sample sizes offer the promise of more accurate and reliable results, they come with their own set of challenges that researchers must navigate carefully. Overfitting and the detection of statistically significant but practically irrelevant differences are two key pitfalls that can compromise the integrity of research findings. Being aware of these issues is crucial for conducting robust and meaningful statistical analyses, underscoring the need for a balanced and thoughtful approach to sample size.

The Importance of Data Quality

In the pursuit of statistical rigor, the focus often shifts overwhelmingly towards increasing the sample size. While a larger sample can offer more robust estimates and greater statistical power, it is not a cure-all solution. One critical aspect that can easily be overshadowed by the allure of large samples is data quality. No matter how large the sample size, biases or inaccuracies in the data can significantly compromise the validity of the analysis.

Larger Sample Size Doesn’t Correct for Biases or Inaccuracies

A common misconception is that a larger sample size will “average out” any biases or inaccuracies present in the data. However, this is not the case. Biases in data collection, measurement errors, or any form of systematic inaccuracies are not corrected by simply increasing the number of data points.

\[\text{Larger Sample Size} \nRightarrow \text{Correction for Biases or Inaccuracies}\]For instance, if a survey has a selection bias where a particular group is overrepresented, increasing the sample size will only amplify this bias. Similarly, if the data contains measurement errors, a larger sample size will not correct these errors but may instead propagate them, leading to misleading conclusions.

The Concept of “Garbage In, Garbage Out”

The principle of “garbage in, garbage out” succinctly captures the essence of the importance of data quality. This concept posits that flawed or poor-quality input will inevitably produce flawed or poor-quality output, regardless of the analytical methods employed.

\[\text{"Garbage In, Garbage Out": Flawed Input} \Rightarrow \text{Flawed Output}\]In the context of statistical analysis, if the data is biased, incomplete, or inaccurate, then the results, too, will be biased, incomplete, or inaccurate. No amount of statistical maneuvering or large sample sizes can turn poor-quality data into reliable findings.

The quality of the data is as important, if not more so, than the quantity represented by the sample size. While large samples can offer many advantages, they cannot correct for poor data quality. Understanding the limitations of large sample sizes and the paramount importance of data quality is essential for conducting meaningful and valid statistical analyses. Therefore, alongside considerations of sample size, equal attention must be given to ensuring the quality and integrity of the data being analyzed.

The Role of Experimental Design

In the realm of research and data analysis, the importance of a well-designed experiment cannot be overstated. While much attention is often given to the size of the sample, the design of the experiment itself is a critical factor that directly impacts the validity and reliability of the results. A poorly designed experiment can introduce biases and errors that no amount of data or sophisticated statistical techniques can correct.

A Well-Designed Experiment is Crucial for Accurate Results

A well-designed experiment serves as the foundation upon which reliable and valid conclusions can be drawn. It ensures that variables are properly controlled or accounted for, that the sample is representative of the population, and that the data collection methods are both accurate and consistent.

\[\text{Well-Designed Experiment} \Rightarrow \text{Controlled Variables, Representative Sample, Accurate Data Collection}\]A well-planned design minimizes the risk of confounding variables, selection biases, and measurement errors, thereby enhancing the integrity of the findings. It sets the stage for the data to be both robust and generalizable, making it a cornerstone of any credible research endeavor.

Common Flaws in Experimental Design

Even with a large sample size, certain flaws in experimental design can significantly compromise the quality of the research. Some common flaws include:

- Confounding Variables: Failure to control for variables that can affect the outcome can lead to spurious results.

- Selection Bias: Non-random or unrepresentative sampling can introduce biases that skew the results.

- Measurement Errors: Inaccurate instruments or flawed data collection methods can introduce systematic errors into the data.

Flaws That Can’t Be Corrected by Increasing Sample Size

Simply increasing the sample size cannot correct these flaws. For instance, if there is a selection bias in the sample, making the sample larger will not make it more representative of the population. Similarly, if there are confounding variables that have not been controlled for, their impact will not be diminished by a larger sample size.

\[\text{Increasing Sample Size} \nRightarrow \text{Correction for Design Flaws}\]The design of the experiment is a critical factor that directly influences the quality of the research. While a large sample size offers many advantages, it is not a substitute for a well-designed experiment. Researchers must pay close attention to the design aspects, from controlling variables to ensuring a representative sample and accurate measurements, to conduct research that is both valid and reliable.

Real-world Implications

The notion that a larger sample size invariably leads to better insights is pervasive across various sectors, from healthcare and economics to technology and social sciences. However, real-world examples often demonstrate that this is not always the case. Moreover, the financial and time costs associated with unnecessarily large sample sizes can be substantial, making it crucial to weigh the benefits against the drawbacks.

Examples from Various Sectors

-

Healthcare: In a clinical trial for a new drug, a large sample size was used to detect even the smallest effects. However, the results, while statistically significant, showed only a negligible improvement in patient outcomes, raising questions about the drug’s practical utility.

-

Finance: In stock market analysis, using a large dataset spanning several decades may seem advantageous. However, such an approach can overlook market regime changes, leading to investment strategies that are not adaptive to current conditions.

-

Technology: In machine learning, using a massive dataset for training can sometimes lead to overfitting, where the model performs exceptionally well on the training data but poorly on new, unseen data.

Financial and Time Costs

Conducting research with a large sample size comes with its own set of challenges, most notably the financial and time costs. Collecting, storing, and analyzing large volumes of data require significant resources. In sectors like healthcare, where clinical trials involve human subjects, the costs can be astronomical. Additionally, the time required to collect and analyze the data can be extensive, delaying the time-to-insight and potentially the time-to-market for new products or therapies.

While large sample sizes offer the allure of more robust and statistically significant results, they are not without their pitfalls. From the risk of detecting statistically significant but practically irrelevant differences to the financial and time costs involved, a larger sample size is not always better. Real-world examples across various sectors underscore the importance of a balanced approach that considers not just the sample size but also the quality of the data and the design of the experiment.

Final Thoughts

The quest for larger sample sizes in statistical analysis is often driven by the well-intentioned aim of achieving more accurate and reliable results. However, as this article has explored, a larger sample size is not a panacea for the complexities and challenges inherent in statistical research. From the risk of overfitting to the detection of statistically significant but practically irrelevant differences, large samples come with their own set of pitfalls. Moreover, they cannot correct for biases, inaccuracies, or flaws in experimental design, emphasizing the principle of “garbage in, garbage out.”

The quality of the data and the design of the experiment are equally, if not more, important than the sheer size of the sample. A well-designed experiment serves as the bedrock of valid and reliable research, setting the stage for data that is both robust and generalizable. Financial and time costs associated with large samples further underscore the need for a more balanced and thoughtful approach.

While the allure of large sample sizes is understandable, a balanced approach that takes into account the quality of the data, the integrity of the experimental design, and the practical implications is essential for conducting meaningful and valid statistical analyses.