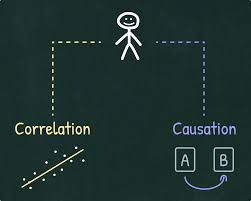

Correlation vs. Causation

Understanding the difference between correlation and causation is key in data analysis, especially in fields where decisions really matter, like medicine, economics, social science, and engineering. Mistaking correlation for causation can lead to costly errors, while correctly identifying causation supports solid, evidence-based decisions.

This article unpacks correlation and causation in detail, covering:

- How correlation shows an association between variables

- Key statistical tools for calculating correlation coefficients

- What causation really means and how to identify it

- Ways to distinguish correlation from causation through experiments and advanced statistical methods

- Real-world examples that highlight the risks of confusing correlation with causation

Introduction to Correlation and Causation

The concepts of correlation and causation are often mixed up. Correlation means we see a relationship between two things—a change in one seems linked with a change in the other. Causation goes a step further, implying that one thing directly causes the other. For anyone using data to make decisions, it’s crucial to get this distinction right to avoid misleading conclusions.

Distinguishing correlation from causation also allows for more rigorous research. Misinterpretations, often due to confounding factors or observational biases, can lead to “spurious” findings—false signals that look meaningful but aren’t. Recognizing genuine causative relationships helps create more accurate models and supports better, informed decision-making.

The Nature of Causation

Causation means there’s a direct cause-and-effect link between two variables: when one changes, it causes the other to change as well. But proving causation is tricky and usually requires controlled methods to avoid influences from outside factors, or “confounders,” that can distort results.

Establishing Cause-and-Effect Relationships

Researchers typically look for three things to establish causation:

- Temporal Precedence: The cause must occur before the effect.

- Covariation of Cause and Effect: There should be a consistent link, where the effect is likely when the cause is present.

- Elimination of Plausible Alternatives: Any other possible causes should be ruled out to confirm the identified cause.

Controlled Experiments

Controlled experiments, especially Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs), are the gold standard for finding causation. In an RCT, participants are randomly assigned to different groups to minimize confounding factors. This setup allows researchers to see whether a treatment or intervention directly affects the outcome.

The Challenges of Proving Causation

Several factors make causation hard to nail down:

- Confounding Variables: Outside factors that influence both variables and can make a link appear causal.

- Observational Bias: In non-experimental data, selection or reporting biases can distort relationships.

- Non-linear Relationships: Complex or non-linear links can be hard to detect using simple correlation measures.

Real-World Examples

Examples from real life show the importance of separating correlation from causation, as mistakes here can lead to flawed policies or strategies.

Case Study: Smoking and Lung Cancer

One classic case is the link between smoking and lung cancer. Early studies found a strong correlation, which led to further investigation through longitudinal and controlled studies. These later studies confirmed that smoking directly caused cancer by exposing tissue to carcinogens, a finding that reshaped public health policy.

Case Study: Vaccination and Autism Myths

A debunked study once suggested a link between vaccines and autism, which fueled vaccine hesitancy. Extensive studies have since shown no causation, yet this misconception highlights how dangerous it can be to confuse correlation with causation.

Case Study: Coffee and Health Benefits

Research often finds that coffee consumption is linked with health benefits, like reduced heart disease risk. But causation hasn’t been established, as factors like diet and activity levels might also contribute.

Key Takeaways

In data analysis, understanding the difference between correlation and causation is essential. Correlation simply shows a relationship, while causation explains what drives it, usually requiring experiments to prove. By interpreting these relationships accurately, analysts can make better decisions and avoid common pitfalls that come from misinterpreting correlation as causation.

Getting this right builds stronger analyses and helps ensure that decisions across fields—whether health, policy, or business—are based on solid evidence.

Appendix: Rust Code Examples for Correlation and Causation Analysis

// Pearson Correlation Coefficient in Rust

fn pearson_correlation(x: &[f64], y: &[f64]) -> f64 {

let n = x.len() as f64;

let sum_x: f64 = x.iter().sum();

let sum_y: f64 = y.iter().sum();

let sum_x_sq: f64 = x.iter().map(|&xi| xi * xi).sum();

let sum_y_sq: f64 = y.iter().map(|&yi| yi * yi).sum();

let sum_xy: f64 = x.iter().zip(y.iter()).map(|(&xi, &yi)| xi * yi).sum();

let numerator = sum_xy - (sum_x * sum_y / n);

let denominator = ((sum_x_sq - (sum_x.powi(2) / n)) * (sum_y_sq - (sum_y.powi(2) / n))).sqrt();

if denominator == 0.0 {

0.0

} else {

numerator / denominator

}

}

// Spearman's Rank Correlation in Rust

fn spearman_rank_correlation(x: &[f64], y: &[f64]) -> f64 {

let rank_x = rank(&x);

let rank_y = rank(&y);

pearson_correlation(&rank_x, &rank_y)

}

fn rank(data: &[f64]) -> Vec<f64> {

let mut indexed_data: Vec<(usize, f64)> = data.iter().cloned().enumerate().collect();

indexed_data.sort_by(|a, b| a.1.partial_cmp(&b.1).unwrap());

let mut ranks = vec![0.0; data.len()];

let mut i = 0;

while i < indexed_data.len() {

let mut j = i + 1;

while j < indexed_data.len() && indexed_data[j].1 == indexed_data[i].1 {

j += 1;

}

let rank = (i + j + 1) as f64 / 2.0;

for k in i..j {

ranks[indexed_data[k].0] = rank;

}

i = j;

}

ranks

}

// Kendall’s Tau in Rust

fn kendalls_tau(x: &[f64], y: &[f64]) -> f64 {

let mut concordant = 0;

let mut discordant = 0;

let n = x.len();

for i in 0..n {

for j in i + 1..n {

let sign_x = (x[i] - x[j]).signum();

let sign_y = (y[i] - y[j]).signum();

if sign_x == sign_y {

concordant += 1;

} else {

discordant += 1;

}

}

}

(concordant - discordant) as f64 / ((n * (n - 1) / 2) as f64)

}

// Example of Granger Causality Calculation

use nalgebra::{DMatrix, DVector};

fn granger_causality(x: &[f64], y: &[f64], max_lag: usize) -> f64 {

let n = x.len() - max_lag;

let mut x_matrix = DMatrix::zeros(n, max_lag);

let mut y_matrix = DMatrix::zeros(n, max_lag);

let mut combined_matrix = DMatrix::zeros(n, 2 * max_lag);

for i in 0..n {

for j in 0..max_lag {

x_matrix[(i, j)] = x[i + j] as f64;

y_matrix[(i, j)] = y[i + j] as f64;

combined_matrix[(i, j)] = x[i + j] as f64;

combined_matrix[(i, j + max_lag)] = y[i + j] as f64;

}

}

let x_model = x_matrix.transpose() * x_matrix;

let y_model = y_matrix.transpose() * y_matrix;

let combined_model = combined_matrix.transpose() * combined_matrix;

let residual_x = DVector::from_element(n, x_model.determinant());

let residual_y = DVector::from_element(n, y_model.determinant());

let residual_combined = DVector::from_element(n, combined_model.determinant());

let f_statistic = ((residual_x - residual_y) / residual_combined).abs();

f_statistic.sum()

}

Appendix: R Code Examples for Correlation and Causation Analysis

# Pearson Correlation Coefficient in R

pearson_correlation <- function(x, y) {

n <- length(x)

sum_x <- sum(x)

sum_y <- sum(y)

sum_x_sq <- sum(x^2)

sum_y_sq <- sum(y^2)

sum_xy <- sum(x * y)

numerator <- sum_xy - (sum_x * sum_y / n)

denominator <- sqrt((sum_x_sq - (sum_x^2 / n)) * (sum_y_sq - (sum_y^2 / n)))

if (denominator == 0) return(0)

return(numerator / denominator)

}

# Spearman's Rank Correlation in R

spearman_rank_correlation <- function(x, y) {

rank_x <- rank(x)

rank_y <- rank(y)

return(pearson_correlation(rank_x, rank_y))

}

# Kendall’s Tau in R

kendalls_tau <- function(x, y) {

n <- length(x)

concordant <- 0

discordant <- 0

for (i in 1:(n-1)) {

for (j in (i+1):n) {

sign_x <- sign(x[i] - x[j])

sign_y <- sign(y[i] - y[j])

if (sign_x == sign_y) {

concordant <- concordant + 1

} else {

discordant <- discordant + 1

}

}

}

tau <- (concordant - discordant) / (0.5 * n * (n - 1))

return(tau)

}

# Granger Causality Example in R

library(lmtest)

granger_causality <- function(x, y, max_lag = 1) {

data <- data.frame(x = x, y = y)

# Create a lagged version of y for Granger causality

for (i in 1:max_lag) {

data[[paste0("y_lag_", i)]] <- c(rep(NA, i), head(y, -i))

data[[paste0("x_lag_", i)]] <- c(rep(NA, i), head(x, -i))

}

data <- na.omit(data)

# Model with y lag terms only

model_y_only <- lm(y ~ ., data = data[, c("y", grep("y_lag", names(data), value = TRUE))])

# Model with x and y lag terms

model_with_x <- lm(y ~ ., data = data[, c("y", grep("y_lag|x_lag", names(data), value = TRUE))])

# Compare models using an F-test for Granger causality

test_result <- anova(model_y_only, model_with_x)

return(test_result["Pr(>F)"][2, ])

}