In the evolving field of credit risk modeling, data drift represents a major challenge that can compromise model reliability. As economic conditions fluctuate, borrowers’ credit behaviors tend to change, leading to significant shifts in the data distribution that predictive models depend on. This article provides a detailed examination of how a credit risk model encountered data drift, the methods used to address the issue, and the resulting improvements in model performance.

Understanding Data Drift in Credit Risk Models

Data drift refers to the phenomenon where the statistical properties of the input data change over time. These changes can degrade a model’s predictive performance by disrupting the relationship between input variables and outcomes. In credit risk modeling, drift can be attributed to various factors, including:

- Economic Changes: Shifts in macroeconomic conditions, such as inflation or unemployment, can influence consumer credit behavior.

- Regulatory Shifts: New regulations in the financial industry may alter lending practices or affect borrower demographics.

- Market Dynamics: The introduction of new financial products or changes in interest rates can lead to shifts in credit usage patterns.

Traditional methods for addressing data drift often focus on univariate analysis, which involves examining each feature in isolation. While useful, this approach can fail to capture more complex interactions between features in a multidimensional space. As a result, important patterns of drift may go unnoticed, leading to model degradation over time.

The Challenge: Degrading Model Performance Over Time

A credit risk model developed using historical borrower data initially demonstrated strong performance. However, after deployment, the model’s performance gradually declined, particularly on out-of-time (OOT) datasets. This decline was reflected in key performance metrics, raising concerns about the model’s applicability to evolving market conditions.

Initial Observations

Several indicators pointed to the presence of data drift:

- Performance Metrics Drop: Key metrics such as the Gini coefficient and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) showed a marked decrease.

- Feature Drift Detection: Using statistical tools like the Jensen-Shannon Distance and Population Stability Index (PSI), significant drift was detected in multiple features.

These observations highlighted the need for a systematic approach to address the drifting features and restore the model’s performance.

First Approach: Addressing Univariate Data Drift

In response to the detected drift, the first approach focused on correcting features that exhibited the most significant univariate drift. This involved identifying the problematic features and removing them from the model.

Steps Taken

- Feature Analysis: Features with high PSI values, indicating substantial changes in their distribution, were identified.

- Feature Elimination: Features exhibiting the highest drift were removed from the model.

- Model Retraining: The model was retrained without the drifting features.

- Performance Evaluation: The retrained model was evaluated using the OOT dataset to assess any improvements in performance.

Outcome

The results of this univariate approach were disappointing:

- No Improvement: The model’s performance remained unsatisfactory, with little to no improvement in the key metrics.

- Loss of Predictive Information: Although the removed features had drifted, they still contained essential predictive information, and their exclusion negatively impacted the model.

These findings highlighted the limitations of univariate analysis. A feature could exhibit drift but still carry crucial information that the model relies on for its predictions. The simplistic approach of removing such features led to a loss of performance rather than an improvement.

A New Approach: Multivariate Data Drift Analysis

Recognizing the limitations of univariate drift analysis, the focus shifted towards understanding drift in a multivariate context. Since credit risk models typically operate in a high-dimensional feature space, it became crucial to analyze how features interact with each other and how these interactions might contribute to data drift.

Methodology

- PCA Reconstruction Error: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed to reduce the dimensionality of the feature space and capture the most important variances in the data. By reconstructing the data based on the principal components, the reconstruction error was used as a proxy for multivariate drift.

- Systematic Feature Evaluation: Each feature was iteratively removed from the dataset, and the PCA reconstruction error was recalculated. This process helped to identify features that contributed significantly to the multivariate drift.

Findings

This multivariate analysis led to the discovery of an unexpected feature:

- Key Feature Identification: A particular feature was found to be a major contributor to multivariate drift. Interestingly, this feature had shown no significant univariate drift and was considered of low importance in the original model.

- Unanticipated Culprit: Despite its apparent stability in univariate analysis, this feature played a key role in interacting with other features, contributing to model instability over time.

Implementing the Solution

Armed with insights from the multivariate analysis, the next step was to modify the model by excluding the identified feature and retraining the model.

Steps Implemented

- Feature Removal: The identified feature was removed from the dataset.

- Model Retraining: The model was retrained without this feature, with a focus on maintaining performance across the remaining features.

- Performance Testing: The retrained model was evaluated on both the in-time and OOT datasets to assess improvements in predictive accuracy and stability.

Results

The results were significant:

- Improved Metrics: The Gini coefficient increased, reflecting better overall performance. The model’s accuracy, particularly on the OOT dataset, improved as well.

- Enhanced Stability: The reduction in multivariate drift contributed to a more stable model, capable of maintaining consistent performance over time.

These outcomes reinforced the idea that focusing on multivariate data drift can be more effective than addressing univariate drift alone. In this case, the removed feature interacted with other features in ways that contributed to hidden drift patterns, which would not have been uncovered through traditional univariate analysis.

Why This Approach Worked

The success of the multivariate approach can be attributed to the complex interactions between features in a high-dimensional space. In credit risk models, features often interact in non-linear ways, amplifying the impact of drift over time. The feature that was ultimately removed acted as a catalyst for this drift due to its interactions with other variables, even though it appeared stable when analyzed in isolation.

Feature Interactions

Complex models, such as those used in credit risk, rely on non-linear interactions between features. Some features may seem stable when viewed independently, but they can still contribute to drift when interacting with other variables.

Hidden Drift

Certain features may mask or exacerbate drift when combined with other features. This kind of hidden drift is difficult to detect with univariate analysis but becomes more apparent in a multivariate context.

Strategies for Addressing Data Drift

Based on this experience, several strategies are recommended for managing data drift in credit risk models:

- Multivariate Drift Analysis: Use advanced methods like PCA reconstruction error or machine learning-based drift detection techniques to capture complex drift patterns across multiple features.

- Feature Importance Reevaluation: Regularly reassess feature interactions and importance. Features that seem insignificant in isolation may still contribute to drift through interactions with other variables.

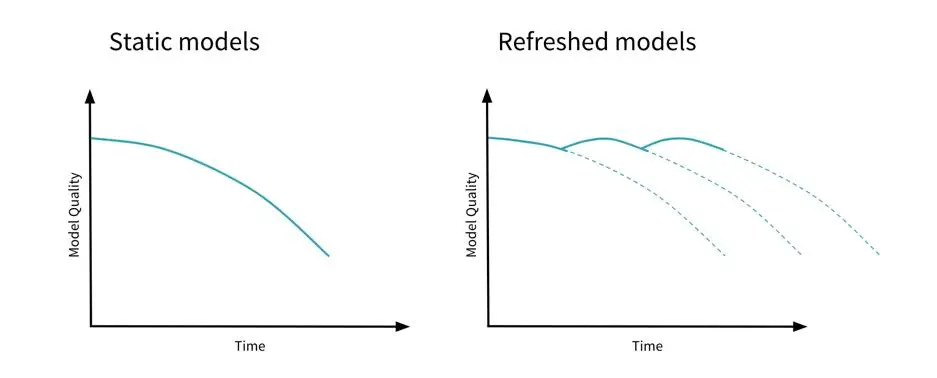

- Model Retraining and Validation: Retrain models regularly using updated datasets. Employ robust validation techniques, incorporating diverse datasets, to ensure the model adapts to new data patterns.

- External Data Incorporation: Augment the dataset with external sources, such as macroeconomic indicators, that capture broader trends in the credit market.

References

- Duboue, P. A. (2020). The Art of Feature Engineering: Essentials for Machine Learning Practitioners. Cambridge University Press.

- Géron, A. (2019). Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow (2nd ed.). O’Reilly Media.

- Thomas, L. C., Edelman, D. B., & Crook, J. N. (2017). Credit Scoring and Its Applications (2nd ed.). SIAM.

- Chhabra, S. (2021). Machine Learning for Credit Risk Modeling: Practitioner’s Approach to Managing Data Drift. Packt Publishing.

- Castillo, C., & D’Souza, N. (2020). Detecting and mitigating concept drift in credit scoring models. Journal of Financial Modeling, 12(3), 45-62.

- Korzyński, M. (2020). Data drift in machine learning models: A review. Machine Learning Journal, 45(5), 123-146.

- Embrechts, P., & Klüppelberg, C. (2014). Multivariate statistical techniques in risk modeling. Risk Analysis Quarterly, 38(2), 34-58.

- Gama, J., Žliobaitė, I., Bifet, A., Pechenizkiy, M., & Bouchachia, A. (2014). A survey on concept drift adaptation. ACM Computing Surveys, 46(4), 44.

- Moody’s Analytics. (2019). Model monitoring for credit risk models. Moody’s Analytics White Paper. Retrieved from Moody’s Analytics

- Population Stability Index (PSI) in credit risk models. (2021). Retrieved from CreditRiskMonitor