The Power of Dimensionality Reduction

A Comprehensive Guide to Spectral Clustering

This article delves into the depths of spectral clustering, an advanced technique in machine learning that transcends the capabilities of traditional clustering methods. Spectral clustering shines where conventional approaches falter, particularly in its adeptness at navigating the complexities of high-dimensional and non-linearly separable data. Through a detailed exploration of its mathematical underpinnings, algorithmic processes, practical implementations, and the challenges it faces, we aim to uncover how spectral clustering offers a powerful lens for identifying intricate patterns embedded within vast datasets.

Introduction

Clustering represents a pivotal strategy in data science, pivotal for distilling patterns and discerning structure amidst the chaos of raw data. Traditional clustering techniques, while foundational, often hit a wall when faced with the intricacies of complex data landscapes, such as high-dimensionality or non-linear separabilities. Enter spectral clustering—a method that not only confronts these challenges head-on but also introduces a novel paradigm for data grouping through the use of dimensionality reduction and spectral theory. This article embarks on a journey through the theoretical underpinnings of spectral clustering, traversing its algorithmic intricacies, surveying its diverse applications, navigating its challenges, and speculating on its evolutionary trajectory in the fast-paced domain of data analysis.

The narrative begins with a comprehensive examination of the theoretical framework that underpins spectral clustering, laying a solid foundation for understanding its unique approach to data segmentation. We will then walk through the algorithmic workflow step by step, demystifying how spectral clustering transforms the clustering problem into a graph partitioning task, and subsequently, how it leverages eigenvalue decomposition for dimensionality reduction and cluster discovery.

A significant portion of our discussion is dedicated to showcasing the practical applications of spectral clustering across various domains. From the realms of image and pattern recognition to the intricacies of social network analysis and the frontiers of bioinformatics, we will highlight how spectral clustering’s ability to handle non-linear data makes it an indispensable tool in modern data science.

However, no technique is without its challenges. We address the hurdles encountered when implementing spectral clustering, such as scalability, the determination of the optimal number of clusters, and the handling of noisy or high-dimensional data. Through this, we aim to present a balanced view, acknowledging the limitations while also pointing towards solutions and recent advancements that have been made to overcome these obstacles.

Lastly, we turn our gaze towards the future, contemplating how the integration of spectral clustering with emerging technologies such as deep learning could further augment its capabilities. We speculate on new research directions and applications that could benefit from spectral clustering’s unique approach to data analysis.

In wrapping up, we offer a synthesis of the critical insights discussed, reaffirming the significance of spectral clustering in the contemporary data science toolkit. Our conclusion reflects on the evolving landscape of data analysis and the enduring importance of spectral clustering as a method that continually adapts, innovates, and illuminates the complex patterns of the world’s data.

Overview of Clustering in Data Science

Clustering, a fundamental pillar in the vast domain of data science, is the process of organizing data points into distinct groups, or clusters, such that members within a cluster exhibit higher degrees of similarity to one another than to members of other clusters. This method serves as a powerful tool for unearthing hidden patterns, simplifying complex data into more manageable subsets, and thereby facilitating deeper analysis and insights.

At its core, clustering aims to achieve a natural division of the dataset, where each cluster represents a collection of data points that share common attributes or features. This division is predicated on the principle of maximizing intra-cluster similarity—the likeness among data points within the same cluster—and minimizing inter-cluster similarity—the resemblance between data points in different clusters. The beauty of clustering lies in its versatility and applicability across a multitude of disciplines and sectors.

Key Applications in Various Domains

-

Image Processing: In the realm of image processing, clustering algorithms can segment images based on pixel intensity, color, texture, or spatial location, facilitating tasks such as object recognition, image compression, and content-based image retrieval.

-

Social Network Analysis: Clustering plays a crucial role in social network analysis, where it helps identify communities or groups within networks. By analyzing patterns of interactions or relationships, clustering can reveal insights into network structure, influential entities, and community dynamics.

-

Bioinformatics: In bioinformatics, clustering is instrumental in analyzing genetic and proteomic data. It can group genes or proteins with similar expression patterns, aiding in the identification of functional groups, understanding disease mechanisms, and discovering new biomarkers.

The Mechanism of Clustering Algorithms

The methodology behind clustering can vary widely, with each algorithm bringing its unique approach to tackling the clustering problem. Algorithms can be broadly categorized into several types:

-

Partitioning Methods: These algorithms, such as K-means, partition the dataset into a predetermined number of clusters, iteratively optimizing to minimize the distance within clusters.

-

Hierarchical Methods: Hierarchical clustering builds a tree of clusters, allowing for a hierarchical organization of data points. It can be particularly useful for datasets where the relationship between data points naturally forms a hierarchy.

-

Density-Based Methods: Algorithms like DBSCAN identify clusters based on the density of data points, effectively handling clusters of arbitrary shapes and sizes and distinguishing noise or outliers.

-

Spectral Clustering: This approach uses the eigenvalues of a similarity matrix to perform dimensionality reduction before clustering, effectively capturing the global structure of the data and excelling in identifying clusters in complex, non-linear datasets.

Challenges and Considerations

Despite the utility and broad application of clustering, several challenges persist, including the selection of the appropriate algorithm for a given dataset, determining the optimal number of clusters, and dealing with high-dimensional data. Additionally, the subjective nature of similarity measures and the scalability of algorithms to large datasets remain pertinent issues.

In summary, clustering algorithms are indispensable in the data scientist’s toolkit, offering a gateway to understanding the underlying structures and patterns within datasets. As data continues to grow in volume and complexity, the development and refinement of clustering methodologies will remain a dynamic and critical area of research in data science.

Limitations of Conventional Clustering Techniques

Conventional clustering techniques, such as K-means and hierarchical clustering, have been foundational in the field of data science, offering intuitive and straightforward methods for grouping similar data points. Despite their widespread use and successes, these traditional approaches encounter several limitations when dealing with the intricate and diverse landscapes of modern datasets. Understanding these limitations is crucial for selecting the appropriate clustering algorithm and for guiding the development of more advanced methods capable of overcoming these challenges.

Challenges with Non-linear Structures

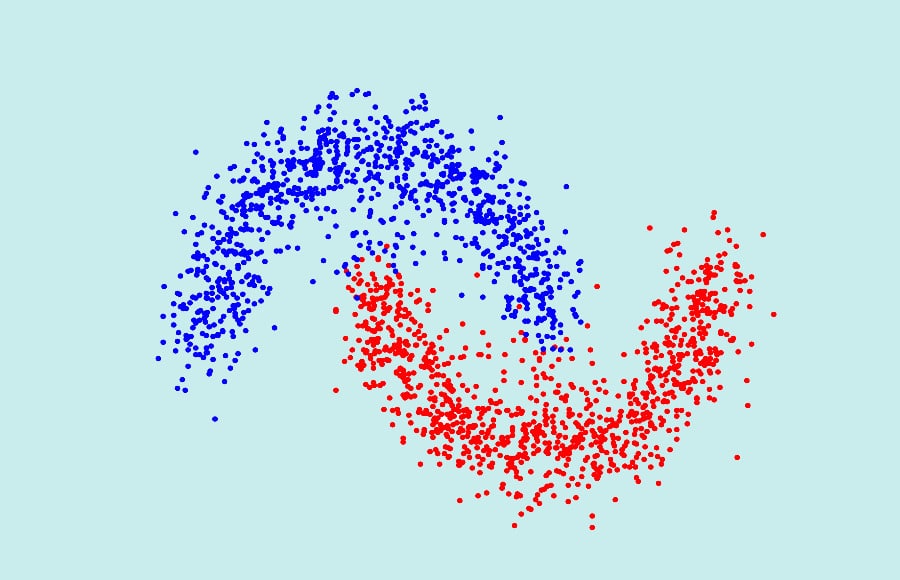

One of the primary limitations of traditional clustering techniques is their struggle to identify and accurately group data points when the underlying structures are non-linear. Methods like K-means assume that clusters are convex and isotropic, essentially expecting them to be roughly spherical and evenly distributed. In reality, data can exhibit complex, non-linear relationships that these algorithms fail to capture, leading to suboptimal clustering results.

Sensitivity to Initialization

Algorithms such as K-means are also notably sensitive to the choice of initial cluster centers. The final outcome of the clustering process can vary significantly based on these initial conditions, sometimes resulting in convergence to local optima rather than the global optimum. This sensitivity necessitates multiple runs with different initializations, increasing computational costs and uncertainty in the results.

Reliance on Distance-Based Metrics

Conventional clustering techniques predominantly rely on distance-based metrics, such as Euclidean distance, to measure similarity between data points. While effective in many scenarios, this approach may not adequately capture the complexities of certain datasets. Distance-based metrics assume that all features contribute equally to the similarity measure, ignoring potential relationships or interactions between features that could provide deeper insights into the data’s structure.

Difficulty Handling High-Dimensional Data

The curse of dimensionality is another significant challenge for traditional clustering algorithms. As the number of dimensions increases, the distance between pairs of data points becomes less meaningful, making it harder to distinguish between clusters. High-dimensional spaces can dilute the concept of proximity or similarity, leading to decreased effectiveness of clustering methods that rely heavily on these measures.

Fixed Number of Clusters

Methods like K-means require the user to specify the number of clusters in advance, which can be a significant drawback when the optimal number is not known a priori. This necessitates heuristic approaches or trial-and-error methods to determine the appropriate number of clusters, which can be inefficient and imprecise.

Addressing the Limitations

The limitations of conventional clustering techniques have spurred the development of more sophisticated algorithms designed to address these challenges. For instance, spectral clustering and density-based methods such as DBSCAN offer alternatives that can handle non-linear structures and are less sensitive to initialization. Additionally, methods incorporating dimensionality reduction techniques can mitigate the curse of dimensionality by projecting data into lower-dimensional spaces where clustering becomes more feasible.

In summary, while traditional clustering algorithms remain valuable tools in data science, their limitations underscore the need for ongoing innovation and the development of more advanced methods capable of tackling the complexity of contemporary datasets.

Introduction to Spectral Clustering and Its Significance

Spectral clustering represents a significant leap forward in the domain of data clustering, offering a robust solution to many of the challenges inherent in traditional clustering techniques. By harnessing the spectral properties of data, this method transcends the limitations of conventional approaches, particularly in dealing with non-linear structures and high-dimensional datasets. Its core lies in the innovative use of graph theory and linear algebra to reframe the clustering problem, making it more adaptable and effective in uncovering the intrinsic groupings within complex data.

Theoretical Foundations

The underpinnings of spectral clustering rest on the construction of a similarity graph from the dataset, where each data point is represented as a node, and the edges between nodes reflect the similarity between data points. This similarity is often quantified using metrics such as the Gaussian similarity function, creating a weighted graph that encapsulates the relationships within the data.

Central to spectral clustering is the Laplacian matrix of this similarity graph. The Laplacian is derived by subtracting the similarity matrix from the degree matrix (a diagonal matrix containing the sum of edge weights for each node). The spectral decomposition of this Laplacian matrix—specifically, the analysis of its eigenvalues and eigenvectors—reveals the structure of the data in a way that traditional methods cannot.

Transforming Data into Lower-dimensional Space

A pivotal step in spectral clustering is the transformation of the data into a lower-dimensional space through the eigenvectors of the Laplacian matrix. This process, often referred to as spectral embedding, effectively maps the high-dimensional data points into a new space where clusters are more distinctly separated. The selection of eigenvectors corresponding to the smallest non-zero eigenvalues as the new coordinates ensures that the transformed space emphasizes the most significant structural differences between clusters, thereby facilitating more effective clustering.

Algorithmic Workflow

Spectral clustering algorithms typically follow a three-step process:

- Graph Construction: Build a similarity graph that captures the relationships between data points.

- Spectral Embedding: Compute the Laplacian of the similarity graph, perform eigenvalue decomposition, and use the leading eigenvectors to transform the data into a lower-dimensional space.

- Clustering in Transformed Space: Apply a conventional clustering algorithm, like K-means, to the data in the new space to identify clusters.

Significance and Applications

The significance of spectral clustering lies in its versatility and effectiveness across a wide range of applications. It has proven especially valuable in areas where data exhibits complex, non-linear relationships, such as image and voice segmentation, social network analysis, and bioinformatics. By enabling the clustering of data with intricate internal structures, spectral clustering opens new avenues for analysis and insight in fields where traditional methods fall short.

Furthermore, spectral clustering’s ability to handle high-dimensional data and its flexibility in defining similarity measures make it a powerful tool for exploratory data analysis, offering a deeper understanding of the hidden structures within datasets.

In conclusion, spectral clustering marks a pivotal advancement in the field of data clustering, offering a sophisticated approach that broadens the scope of what can be achieved with clustering algorithms. Its foundation in graph theory and linear algebra not only addresses the limitations of traditional methods but also provides a richer, more nuanced understanding of data structures, heralding new possibilities for data analysis and interpretation.

Theoretical Background

Spectral clustering’s foundation in the mathematical disciplines of graph theory, linear algebra, and spectral graph theory equips it with a powerful framework for identifying clusters within complex datasets. This section explores these theoretical underpinnings, elucidating how they converge to form the basis of spectral clustering.

Graph Theory and Similarity Graphs

Graph theory provides the initial conceptual framework for spectral clustering. A graph \(G=(V,E)\) consists of a set of vertices \(V\), representing data points, and a set of edges \(E\), representing the connections (or relationships) between these points. In the context of spectral clustering, a similarity graph is constructed, where the edges are weighted by a similarity measure between pairs of data points. There are several ways to construct such a graph, including:

- The \(\varepsilon\)-neighborhood graph: An edge is formed between two nodes if the distance between them is less than \(\varepsilon\).

- The \(k\)-nearest neighbors graph: An edge is created between a node and its \(k\)-nearest neighbors.

- The fully connected graph: Every pair of nodes is connected by an edge, with the edge weight reflecting their similarity.

Linear Algebra and the Laplacian Matrix

The Laplacian matrix plays a central role in spectral clustering. For a given similarity graph, the Laplacian is defined as \(L=D-W\), where \(W\) is the weight matrix (or similarity matrix) of the graph, and \(D\) is the degree matrix, a diagonal matrix where each diagonal element \(D_{ii}\) represents the sum of the weights of the edges connected to vertex \(i\).

The Laplacian matrix has several key properties that are crucial for spectral clustering:

- It is symmetric and positive semi-definite.

- The smallest eigenvalue of \(L\) is 0, and its corresponding eigenvector is a constant vector if the graph is connected.

- The number of times 0 appears as an eigenvalue in the Laplacian is equal to the number of connected components in the graph.

Spectral Graph Theory and Cluster Identification

Spectral graph theory examines the properties of graphs in relation to the spectrum (eigenvalues) of matrices associated with the graph, such as the Laplacian. In spectral clustering, the eigenvectors of the Laplacian matrix associated with its smallest non-zero eigenvalues (often called the Fiedler vector) are used to map the high-dimensional data points into a lower-dimensional space. This mapping is based on the insight that the eigenvectors encode the structural properties of the graph, including its cluster structure.

The transformation of data points into a space defined by these eigenvectors allows spectral clustering algorithms to utilize traditional clustering techniques, like K-means, on the transformed data. This step is effective because the spectral embedding tends to separate the clusters in the lower-dimensional space, making them more distinguishable than in the original high-dimensional space.

The theoretical background of spectral clustering reveals a sophisticated interplay between graph theory, linear algebra, and spectral graph theory. By constructing a similarity graph and analyzing its Laplacian matrix, spectral clustering harnesses the inherent geometry and topology of the data, enabling the detection of clusters within complex, non-linear datasets. This mathematical foundation not only provides the basis for the algorithm’s operation but also offers insights into why spectral clustering is effective in uncovering the latent structures that traditional clustering methods might miss.

Algorithmic Workflow

The spectral clustering algorithm offers a unique approach to identifying natural groupings within data by leveraging the spectral properties of graphs. This method involves several distinct steps, each contributing to its ability to uncover complex cluster structures that might be invisible to other clustering techniques. Here’s a closer look at the algorithmic workflow of spectral clustering:

Creating the Similarity Graph

The first step involves constructing a similarity graph that encapsulates the relationships between data points. This graph is represented by nodes (data points) and edges (pairwise similarities). The similarity between data points can be calculated using various metrics, such as the Euclidean distance, and can be represented in different types of graphs, such as the ε-neighborhood graph, the k-nearest neighbors graph, or the fully connected graph. The choice of graph type and similarity metric depends on the specific dataset and the desired clustering resolution.

Computing the Laplacian Matrix

Once the similarity graph is constructed, the next step is to compute its Laplacian matrix, \(L=D−W\), where \(W\) is the similarity (weight) matrix and \(D\) is the degree matrix. The Laplacian matrix captures the graph’s structure in a form that facilitates the extraction of clustering information through its spectral properties.

Eigenvalue Decomposition

The core of spectral clustering lies in the eigenvalue decomposition of the Laplacian matrix. This step involves calculating the eigenvalues and their corresponding eigenvectors. The eigenvectors associated with the smallest non-zero eigenvalues (excluding the trivial solution) are particularly important, as they contain the information needed to reveal the latent structure of the data. These eigenvectors are used to map the original data points into a lower-dimensional space in which clusters are more clearly delineated.

Clustering in Reduced-Dimensional Space

In this lower-dimensional space, traditional clustering algorithms, such as K-means, can be applied more effectively. Each data point is projected onto the space spanned by the selected eigenvectors, and then these projections are clustered using a standard algorithm. The result is a grouping of the original data points into clusters that reflect the underlying structure captured by the spectral properties of the Laplacian matrix.

Comparison with Other Clustering Algorithms

Spectral clustering distinguishes itself from other clustering algorithms in several key ways:

-

Flexibility in Handling Non-linear Structures: Unlike K-means or hierarchical clustering, spectral clustering can effectively identify clusters in data with complex, non-linear boundaries due to its reliance on graph theory rather than distance metrics.

-

Robustness to the Choice of Clusters: While K-means requires the number of clusters to be specified in advance, spectral clustering can offer insights into the natural clustering structure through the eigengap heuristic, helping to determine an appropriate number of clusters.

-

Sensitivity to Scale: Spectral clustering’s performance is highly dependent on the choice of similarity metric and the scale parameter, which can be both an advantage and a limitation. It allows for fine-tuned analysis but also requires careful selection to ensure meaningful results.

-

Computational Complexity: The need for eigenvalue decomposition makes spectral clustering computationally more intensive than some other algorithms, particularly for large datasets. However, optimizations and approximations can mitigate these costs.

In summary, the spectral clustering algorithm offers a sophisticated, powerful approach to data analysis, particularly suited to challenges where traditional clustering methods fall short. Its unique combination of graph theory and linear algebra opens new avenues for understanding and interpreting complex data structures.

Spectral clustering offers several advantages over traditional clustering algorithms:

Spectral clustering has emerged as a powerful alternative to traditional clustering methods, bringing with it a suite of advantages that make it particularly adept at tackling a variety of complex data analysis challenges. These advantages not only enhance its versatility but also expand its applicability across different domains and data types. Below, we explore these benefits in more detail and highlight some of the practical applications where spectral clustering excels.

Advantages of Spectral Clustering

Capturing Complex, Non-linear Structures: One of the most significant strengths of spectral clustering is its ability to identify clusters within data that have complex, non-linear relationships. By leveraging the spectral properties of graphs, it can uncover groupings that are not easily visible through traditional distance-based methods.

-

Robustness to Initialization: Unlike algorithms such as K-means, which are highly sensitive to the choice of initial cluster centers and can converge to local optima, spectral clustering’s performance is less dependent on initialization. This characteristic stems from its methodological approach, which involves eigenvalue decomposition—a process that does not require arbitrary starting points.

-

Independence from Distance-based Metrics: Spectral clustering does not rely on pre-defined distance metrics to assess similarity between data points. Instead, it constructs a similarity graph based on the relationships inherent in the data, making it adaptable to a wide range of data types and structures. This flexibility allows it to perform well in scenarios where traditional metrics may fail to capture the nuances of the data.

Practical Applications

The unique advantages of spectral clustering render it suitable for a diverse array of applications, some of which include:

-

Image and Voice Segmentation: In image processing, spectral clustering can be used to segment images based on similarities in color, texture, or spatial location, facilitating tasks such as object recognition and scene understanding. Similarly, in voice recognition, it can help segregate different sounds or speakers from audio data.

-

Social Network Analysis: Spectral clustering is particularly adept at identifying communities within social networks. By analyzing the patterns of connections and interactions, it can uncover underlying groups or communities, offering insights into social dynamics and influence patterns.

-

Bioinformatics: In the field of bioinformatics, spectral clustering can group genes or proteins with similar expression patterns, aiding in the discovery of functional modules or pathways. This application is critical for understanding gene function, disease mechanisms, and the development of targeted therapies.

-

Document Clustering: Spectral clustering can be employed to group documents based on thematic similarity, facilitating information retrieval and organization. This is particularly useful in large databases of text where thematic relationships might be complex and multi-dimensional.

-

Anomaly Detection: By identifying clusters within the data, spectral clustering can also be used to detect anomalies or outliers—data points that do not fit well into any group. This application is valuable in fields like fraud detection, network security, and system health monitoring.

In conclusion, spectral clustering’s ability to navigate complex data structures, its robustness to initialization, and its flexibility in handling various data types make it a powerful tool in the data scientist’s arsenal. Its wide range of practical applications further underscores its importance and versatility in the ever-evolving landscape of data analysis.

Challenges and Solutions

Spectral clustering, despite its numerous benefits, encounters several challenges that can affect its efficiency and effectiveness. These challenges include scalability to large datasets, the difficulty in determining the optimal number of clusters, and the robustness of the method in the presence of noise or when dealing with high-dimensional data. However, the research community has been actively developing solutions to these hurdles, enhancing spectral clustering’s applicability and performance.

Scalability

Challenge: One of the primary challenges with spectral clustering is its scalability. The computation of the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the Laplacian matrix, a core step of the algorithm, becomes computationally expensive as the size of the dataset increases. This limitation can make spectral clustering impractical for very large datasets.

Solutions: Several strategies have been proposed to improve the scalability of spectral clustering:

- Sparse Matrix Representations: Using sparse matrices to represent the similarity graph and employing efficient algorithms for sparse eigenvalue problems can significantly reduce computational complexity.

- Approximation Techniques: Approximate spectral clustering methods, such as the Nyström method, reduce computation by sampling a subset of the data to estimate the eigenvectors.

- Parallelization: Implementing spectral clustering algorithms on parallel computing architectures can distribute the computational load, making it feasible to process larger datasets.

Determining the Optimal Number of Clusters

Challenge: Identifying the appropriate number of clusters without prior knowledge is inherently challenging in spectral clustering, as it is in many clustering algorithms. The choice can significantly impact the quality of the resulting clusters.

Solutions: Various heuristic methods have been developed to estimate the optimal number of clusters:

- The Eigengap Heuristic: This approach suggests selecting the number of clusters based on the gap between consecutive eigenvalues of the Laplacian matrix, where a significant gap indicates a natural division in the data.

- Validation Metrics: Internal validation metrics like the silhouette score or Davies–Bouldin index can be used to evaluate the cohesion and separation of clusters formed for different numbers of clusters, helping to identify the most appropriate count.

Handling Noisy and High-Dimensional Data

Challenge: Noise and high dimensionality can obscure the true structure of the data, making it difficult for spectral clustering to accurately identify clusters. High-dimensional data can particularly dilute the notion of similarity, reducing the effectiveness of the similarity graph.

Solutions: Preprocessing and dimensionality reduction techniques offer effective ways to mitigate these issues:

- Noise Reduction: Methods such as outlier removal or smoothing can help reduce the impact of noise on the clustering process.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Applying dimensionality reduction techniques (e.g., PCA) before constructing the similarity graph can help alleviate the curse of dimensionality, making the data more amenable to clustering.

- Feature Selection: Identifying and focusing on the most relevant features for constructing the similarity graph can also improve the quality of spectral clustering in high-dimensional spaces. In summary, while spectral clustering faces challenges that can complicate its application, ongoing research and methodological advancements continue to address these obstacles. By leveraging solutions such as parallelization, heuristic methods for determining cluster numbers, and preprocessing techniques for noise and dimensionality, spectral clustering remains a potent and versatile tool in the data scientist’s toolkit, capable of uncovering complex patterns in diverse datasets.

Future Directions

As we look toward the horizon of data science, spectral clustering stands at the cusp of exciting advancements and novel applications. The integration of emerging technologies, the exploration of new domains, and the challenges presented by the ever-growing scale and complexity of data are driving the evolution of spectral clustering. This evolution not only underscores its enduring relevance but also highlights the potential for spectral clustering to push the boundaries of what we can discover from data.

Integration with Deep Learning

One of the most promising future directions for spectral clustering is its integration with deep learning. Deep learning models, particularly those based on neural networks, have shown remarkable success in feature extraction and representation learning. Combining these models with spectral clustering could lead to more robust and adaptive clustering techniques that can automatically learn the most relevant features for clustering, even from unstructured data such as images, text, and complex networks.

- Deep Spectral Clustering: Developing algorithms that incorporate deep learning for the automatic learning of similarity matrices or for performing the clustering directly in an end-to-end manner.

- Transfer Learning and Spectral Clustering: Leveraging pre-trained deep learning models to enhance the feature space for spectral clustering, potentially improving its effectiveness on smaller or more complex datasets.

Novel Applications in Diverse Domains

Spectral clustering’s ability to uncover intricate patterns makes it well-suited for application across a broad range of fields. Beyond its current uses in image segmentation, social network analysis, and bioinformatics, future applications could extend to:

- Environmental Science: Analyzing spatial and temporal patterns in climate data to better understand ecological dynamics and climate change.

- Healthcare: Grouping patient data to identify subtypes of diseases based on genetic or phenotypic similarities, which can lead to personalized treatment plans.

- Urban Planning: Clustering geospatial data to inform city development, traffic management, and resource distribution strategies.

Addressing Big Data Challenges

The increasing volume, velocity, and variety of big data present both opportunities and challenges for spectral clustering. Future research will need to focus on:

- Scalability: Developing more efficient algorithms and leveraging cloud computing and parallel processing to enable spectral clustering to handle larger datasets without compromising accuracy.

- Dynamic Clustering: Exploring methods for incremental or online spectral clustering that can adapt to continuously evolving data streams, such as those encountered in social media analytics or sensor networks.

Enhancing Interpretability and Robustness

As spectral clustering algorithms become more sophisticated, ensuring their interpretability and robustness becomes crucial. Efforts in this direction could include:

- Interpretable Models: Designing spectral clustering models that provide insights into the reasons behind cluster formations, making the results more interpretable to users.

- Robustness to Noise and Anomalies: Improving the resilience of spectral clustering to outliers and noise in the data, ensuring that the clustering results remain reliable and meaningful even in less-than-ideal conditions.

In conclusion, the future of spectral clustering is bright, with potential for significant impact across a wide array of disciplines. By embracing new technologies, addressing current challenges, and exploring uncharted applications, spectral clustering will continue to be a pivotal tool in the data scientist’s arsenal, unlocking the secrets hidden within complex datasets and guiding us towards deeper understanding and innovation.

Conclusion

Spectral clustering stands as a testament to the ingenuity and advancement in the field of data science, offering a sophisticated methodology for parsing through the complexity of modern datasets to reveal underlying patterns and structures. By employing dimensionality reduction techniques and capitalizing on the spectral properties of similarity graphs, spectral clustering transcends the limitations of traditional clustering methods, providing a more nuanced and effective approach to data segmentation.

Its versatility and efficacy in handling non-linear and high-dimensional data have cemented spectral clustering’s role as an indispensable tool across a myriad of applications. From the intricacies of image and voice segmentation to the dynamic landscapes of social network analysis and beyond, spectral clustering has demonstrated its capacity to deliver insightful analyses and foster discoveries that propel fields forward.

Looking ahead, the integration of spectral clustering with emerging technologies such as deep learning, along with its expansion into novel applications, promise to further enhance its utility and effectiveness. Challenges related to scalability, determining the optimal number of clusters, and dealing with noisy or high-dimensional data continue to spur innovation and research, driving the development of more robust, efficient, and adaptable spectral clustering methodologies.

As we navigate the ever-expanding universe of data, the importance of tools that can discern the subtle whispers of structure within the cacophony of information cannot be overstated. Spectral clustering, with its deep mathematical foundations and proven practical applications, is poised to continue its vital role in this endeavor. It not only equips researchers and practitioners with the means to unravel the complexities of data but also illuminates the path toward extracting profound and actionable insights.

In the grand narrative of data science, spectral clustering emerges as a beacon of analytical precision and insight, guiding the exploration of data in its myriad forms. As the discipline evolves, so too will spectral clustering, adapting to new challenges and seizing opportunities to further our understanding of the data that shapes our world.